A network port is a logical address used by computers to route data to specific applications or services. Ports operate at the transport layer (Layer 4) of the TCP/IP model and allow a single IP address to host multiple network services. For example, HAProxy explains that a port “is a communications channel between two computers” often bound to a specific service. Each port is identified by a 16-bit number (0–65535) appended to the IP address (e.g. 192.168.1.10:80). This lets the host’s TCP or UDP implementation know which application should handle incoming packets: only the host inspects the port number to route the data internally. In other words, IP addresses route packets to the right machine, while port numbers direct them to the correct program on that machine.

A common analogy is that an IP address is like a street address or building, and the port is like an apartment or office number. Just as only the recipient at a given address needs to see the apartment number, only the receiving host “looks” at the port number to deliver the data. Cloudflare notes that ports are a transport-layer concept – IP packets themselves have no field for a port number. In fact, pinging an address (ICMP) can check if a host is alive but cannot target a specific port. Instead, once a TCP or UDP packet reaches its destination IP, its header’s destination port field tells the OS which program’s socket should receive the data. For instance, a packet to port 80 will be handed to the web server process, while a packet to port 21 goes to the FTP service. This demultiplexing of services is how multiple network applications (web server, email server, etc.) can run on a single machine simultaneously.

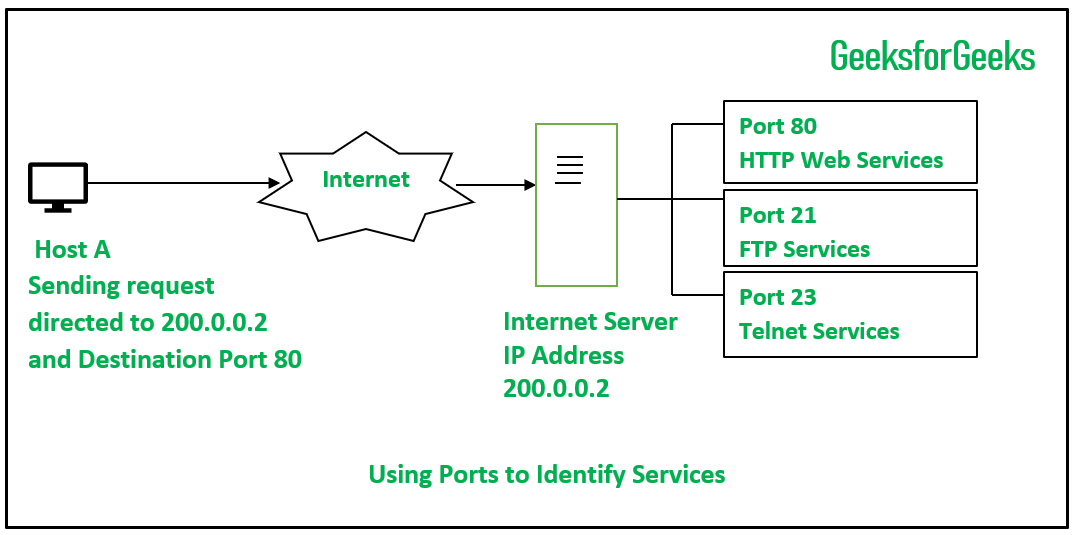

Figure: Example showing how port numbers direct traffic to specific services on a host. A packet sent to IP 200.0.0.2 at port 80 is routed to the host’s web (HTTP) server, while sending it to port 21 would reach its FTP service, and port 23 its (unencrypted) Telnet service. Port numbers thus act like “extensions” or “mail slots” on an IP address, guiding incoming packets to the correct application.

How Ports Work

When data is sent over the network, the sending application provides a source port (chosen from the ephemeral range) and a destination port (the well-known port of the target service). Each host maintains a table that maps listening processes to specific port numbers. For example, a web server process will register (or “listen”) on port 80 so it can receive HTTP requests. If a packet arrives with destination port 80, the host’s TCP stack hands it to the web server. If it had port 21 instead, the OS would deliver it to the FTP server process.

Ports fall into well-known ranges by convention. Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) defines ports 0–1023 as system or well-known ports (assigned to standard services), ports 1024–49151 as user/registered ports, and 49152–65535 as dynamic or private (ephemeral) ports. (Port 0 is reserved and generally unused.) Common services listen on standard ports in the 0–1023 range, while client applications use an available ephemeral port above 1023 for the source. In practice, when you make an outgoing connection, your OS picks an unused port in 1024–65535 as the source port. The remote server sees this ephemeral port as the reply address. For example, when you visit a website, your browser might use source port 52678 to connect to the server’s port 80. The server then replies back to your IP at port 52678, thus completing the bidirectional communication.

Ports can use either TCP or UDP as the underlying transport protocol. TCP (Transmission Control Protocol) is connection-oriented: it establishes a reliable byte-stream between endpoints. TCP splits data into segments, numbers them, and requires acknowledgements; lost packets are retransmitted. For instance, HAProxy notes that TCP “ensures reliable in-order delivery” by sending ACKs and resending lost segments. This makes TCP suitable for services where data integrity matters (web pages, emails, file transfers, etc.). On the other hand, UDP (User Datagram Protocol) is connectionless: each packet (datagram) is sent independently without handshake or guarantee of delivery. UDP simply attaches port numbers and sends datagrams; it does not ensure they arrive or arrive in order. Because of its lightweight nature, UDP is used when low latency is more important than reliability (e.g. DNS queries, video streaming, online gaming, VoIP).

The table below summarizes key differences:

-

TCP (Ports): Connection-oriented stream, reliable, in-order delivery with retransmissions. Used by web (HTTP/HTTPS), SSH, SMTP, FTP control channel, etc.

-

UDP (Ports): Connectionless datagrams, unreliable, no ordering. Used by DNS (queries usually over UDP), SNMP, streaming protocols, online gaming, etc. UDP packets carry only port numbers plus a simple checksum.

TCP and UDP both use 16-bit port numbers, so in principle TCP port 80 and UDP port 80 can coexist on the same host (though typically services use one protocol or the other). Importantly, routers and the network layer do not examine ports. Only when a packet reaches the end host do the TCP/UDP headers get processed. As Cloudflare explains, the IP layer is “unaware” of port numbers – they are purely part of the transport-layer header.

Common Port Numbers and Their Uses

Many services have well-known port assignments. Below are some commonly encountered ports and the protocols that use them:

-

Port 80 (TCP): HTTP web traffic (unencrypted).

-

Port 443 (TCP): HTTPS (HTTP over TLS/SSL, secure web traffic).

-

Port 53 (UDP/TCP): DNS (Domain Name System) – usually UDP for queries, TCP for larger transfers.

-

Port 21 (TCP): FTP control (command channel).

-

Port 20 (TCP): FTP data (in active mode; the client’s data connection back to server).

-

Port 22 (TCP): SSH (Secure Shell) for remote login and secure file transfer (SFTP).

-

Port 23 (TCP): Telnet (unencrypted remote login, largely obsolete).

-

Port 25 (TCP): SMTP (Simple Mail Transfer, email relay).

-

Port 587 (TCP): SMTP (email submission with TLS).

-

Port 110 (TCP): POP3 (Post Office Protocol v3) for retrieving email. Port 995 is POP3S (POP3 over SSL).

-

Port 143 (TCP): IMAP (Internet Message Access) for email. Port 993 is IMAPS (IMAP over SSL).

-

Port 123 (UDP): NTP (Network Time Protocol) for time synchronization.

-

Port 137–139, 445 (TCP/UDP): SMB/CIFS (Windows file sharing).

-

Port 3389 (TCP/UDP): RDP (Remote Desktop Protocol).

-

(And many more are defined by IANA and RFCs).

These assignments are by convention (and often controlled by IANA). For example, IANA states that “System (well-known) Ports” are 0–1023, which are assigned via standard processes. Ports 1024–49151 can be registered for applications, and 49152–65535 are dynamic/private (often used as ephemeral ports). For instance, according to Akamai, port 80 is standardized for web servers and port 443 for HTTPS. The table above is not exhaustive, but these values cover the most common services. (As noted, ports like 587 have become common for SMTP submission, replacing 25 for encrypted mail.) By using these standard ports, clients and servers can interoperate without custom configuration.

Ports, IP Addresses, and Data Transmission

In network communication, a socket is often defined by a tuple: (source IP, source port, destination IP, destination port). When you send data, the packet carries both your IP and port as the source and the remote IP and port as the destination. Routers on the Internet see only the IP addresses and forward packets based on that. Once the packet arrives at the destination IP, the host’s TCP/UDP layer looks at the destination port to deliver the payload to the correct application. This separation of addressing responsibilities is crucial. For example, only devices on the final local network need to inspect the entire IP address; upstream routers need only match the network prefix to route packets. Similarly, the host is the only entity that inspects the destination port and hands data to the right program.

It’s also important to note how ports interact with firewalls and NAT. Firewalls often allow or block traffic based on port numbers and protocols. For instance, a firewall rule may block incoming traffic to port 23 (Telnet) on your system to prevent unwanted remote logins. Network Address Translation (NAT) uses port mapping: a router can forward incoming traffic on, say, public port 8080 to an internal IP’s port 80, allowing multiple internal hosts to be accessed via different external ports. Regardless of NAT, the concept of port-to-service routing remains the same once a packet reaches its final host.

Lastly, clients usually use ephemeral ports (as mentioned above). When a TCP connection is established, both ends use port numbers, but the client’s port is typically ephemeral. For example, a web browser on your PC might connect from local port 53421 to server port 443. The server sees it as a connection from <yourIP>:53421 to <serverIP>:443. Because port numbers and IPs are stored in the TCP/IP header, replies from the server are correctly routed back to the browser’s socket.

Open, Closed, and Filtered Ports

The state of a network port can be open, closed, or filtered, especially in the context of scanning and firewall policies. According to the Nmap security scanner documentation, these terms mean:

-

Open: An application is actively accepting TCP connections (or UDP datagrams) on that port. This means a service is listening. Open ports are the main concern in security, since each open port is “an avenue for attack”. Administrators often secure open ports with firewalls or shunt traffic through proxies to control access.

-

Closed: The port is accessible but no application is listening. The host will receive the packet and typically reply with a TCP RST (reset) packet. A closed port indicates the host is up (since it responds) but not offering that service. One can scan closed ports without enabling new services.

-

Filtered: A firewall or filter is preventing the probe from reaching the port. Nmap calls a port filtered if it cannot determine whether it is open or closed because the probes are blocked. Firewalls often drop packets silently (or send ICMP unreachable responses), causing scanners to label such ports filtered. This “stealth” behavior (no response) frustrates attackers.

Figure: Example of a port scan using a tool like nmap. The scanner probes a host across many ports to see which respond. Open ports (shown in green) are those where a service acknowledged the request. Other ports may appear closed (receiver sent a reset) or filtered (no response due to firewall).

Because open ports imply running services, attackers routinely perform port scans to identify targets. Palo Alto Networks notes that a port scanner “probes a host or server to identify open ports” and that “bad actors can use port scanners to exploit vulnerabilities”. Firewalls and intrusion detection systems watch for such scans. For example, Akamai recommends blocking or disabling unused ports to reduce attack surface. Common attack vectors include protocols with known exploits (e.g. RDP on port 3389, SMB on 445, etc.). As one security FAQ observes, port 3389 (RDP) is a well-known attack vector, so exposing it to the Internet without protection invites ransomware and other hacks.

Network administrators use scanning themselves for defense. A scan revealing an unexpected open port may indicate misconfiguration or compromise. By contrast, a filtered or silent port on a secure firewall gives an attacker little information about what (if anything) is behind it. The Nmap documentation emphasizes that security teams know “each open port is an avenue for attack” and strive to close or protect them. In practice, typical firewall policy is to allow only essential ports (such as 80, 443 for web servers, 25/587 for mail servers, 22 for SSH, etc.) and block all others.

Practical Examples

Web Browsing: When you browse the web, your browser uses TCP. It opens a connection from a random ephemeral port on your computer to the server’s port 80 (HTTP) or 443 (HTTPS). For example, if you visit example.com, your browser might use local port 52345 to connect to 93.184.216.34:80. The web server listening on port 80 receives the request and sends back the webpage data. TCP ensures that data arrives reliably. The browser’s OS, seeing the reply to port 52345, delivers it to the browser. In this way, multiple web pages, email checks, and other applications can run simultaneously: they each have their own port pair.

Email: Sending email typically uses SMTP. Traditionally SMTP servers listen on TCP port 25 for server-to-server mail. However, modern mail clients submit outgoing mail on port 587 (with TLS) or 465 (SMTPS). Retrieving email uses protocols like IMAP or POP3 on their ports. For example, an IMAP server listens on TCP port 143 (or 993 for IMAPS), while a POP3 server uses port 110 (or 995 for POP3S). If you check mail, your email client will connect from an ephemeral port to the server’s port (e.g. 993) and log in. The email server’s reply goes back to your client’s port. Ports thus keep your SMTP (outgoing) traffic separate from IMAP (incoming) and from other traffic.

File Transfer: The classic FTP service uses two ports: the client establishes a TCP connection from its ephemeral port to server port 21 (the FTP command port). The server’s response and commands go back to the client. Data transfers use port 20 (in active mode) or a negotiated port in passive mode. Secure file transfer (SFTP) uses SSH on port 22. When you transfer a file via SFTP or SCP, your client connects to port 22 on the server, establishing an encrypted channel. The OS uses the port number to hand the packets to the SSH service rather than any other program.

Streaming and Gaming: Media streaming and games often use UDP to reduce latency. For instance, live video conferencing or gaming might use RTP/UDP protocols on various high-numbered ports. According to NordVPN, “UDP is a great option if you are gaming, streaming, or using VoIP services” because losing a few packets does not ruin the experience, while using TCP could introduce lag. Similarly, content streaming services (e.g. Netflix) use HTTP streaming over TCP (since they buffer and prioritize reliability), but multiplayer games commonly use UDP on specific ports. (Many routers have port forwarding guides for popular games, e.g. forwarding UDP port 3074 for Xbox Live, etc.) In any case, the client and server agree on which port to use, so that all media packets are correctly routed.

Others: Many other applications rely on ports. For instance, network time synchronization uses UDP port 123 (NTP); database servers like MySQL often use port 3306; chat and VoIP applications may use various ports. On the host side, you might see multiple listening services. Using tools like netstat or ss on Linux, you can list all open (TCP/UDP) ports and see which services are bound to them, illustrating how the OS ties ports to applications.

In all cases, ports serve as logical endpoints. When data traverses the network, the transport header includes the destination port so that at the receiving host the kernel knows which process (which socket) should receive the incoming bytes. Likewise, the source port identifies the local application on replies. This mechanism is fundamental to how the Internet works: it enables multiplexing of many services over a single IP and makes it possible to run web servers, mail servers, databases, and more all at once.

0 Comments